Haustor released their debut LP in 1981 through Jugoton. Formed just two years earlier in Zagreb by the charismatic duo of Darko Rundek and Srđan Sacher, they arrived already brimming with ideas. Boris Leiner of Azra even played drums during their early phase, though he soon left to focus solely on Azra. Compared to the raw chaos of Šarlo Akrobata (whose Bistriji ili tuplji čovek biva kad… we recently reviewed), Haustor feels immediately more accessible, more melodic, even friendly. But underneath the pop-rock hooks and the two-tone bounce, there’s an undeniable weirdness — an eccentric edge that keeps you just slightly off balance.

That’s no accident. Rundek, who had switched his academic focus to directing at the Zagreb Academy of Dramatic Art, brought a flair for pantomime, costume, and drama into the band’s DNA. Meanwhile, Sacher, deep in his studies of archaeology and ethnology, wove ethnic sounds — both Yugoslav and global — into their new wave foundation. It’s this balance of theatricality and ethnographic curiosity that gives Haustor its distinct flavour.

The reggae and two-tone influences initially caught me off guard. Coming from London, where reggae has long been part of our cultural bloodstream thanks to the Windrush generation, it was surreal to hear similar sounds reinterpreted through a Zagreb lens. But while The Specials or Madness might come to mind, Haustor carry a deeper existential weight — darker, weirder, more Ex-YU, if you will.

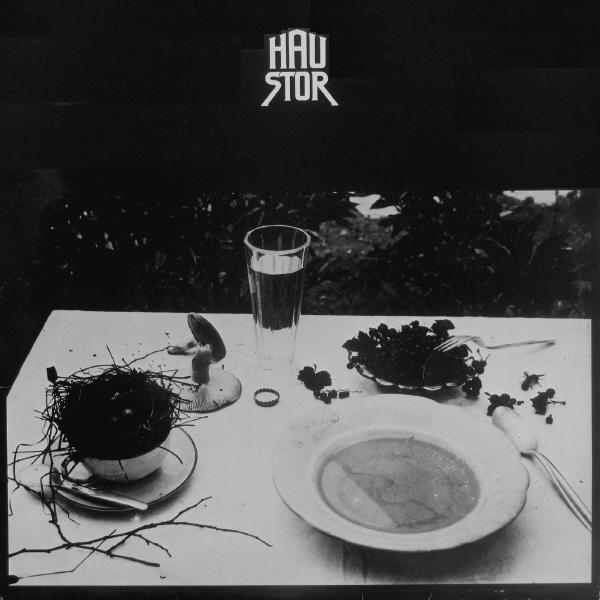

And it wasn’t just the music that left a mark. The album cover — a minimalist black-and-white photo of a table set with mushrooms, a glass of water, and twigs in a mug — has since become iconic, even ranking fifth on Balkan Rock’s list of greatest covers. It’s homely, surreal, and oddly theatrical — perfectly fitting for the band’s early aesthetic.

Production was handled by Parni Valjak’s Husein Hasanefendić “Hus”, and while the album feels a bit raw in places, there’s a livewire energy running through it. One song, Radnička klasa odlazi u raj, named after the 1971 Elio Petri film, was removed from the record under pressure from Yugoslavia’s Secretariat for Culture. It’s a subtle reminder that even in their earliest days, Haustor weren’t afraid to push boundaries.

The first half of the album is an upbeat cocktail of new wave, pop rock, and reggae influence. Radio kicks things off lightly — it’s fun, catchy, nothing too complex, and it sets the stage. Then Mijenjam Se arrives, sharp and swift, driven by a skittering rhythm and saxophone bursts. It brings to mind early Talking Heads with a two-tone twist. Tko Je To follows similarly but adds some subtle keys and slick guitar work that make it arguably catchier than its predecessor.

Then comes ‘60 – ‘65, where whispered vocals ride atop a slow ska rhythm and bold brass section. It’s one of the more haunting tracks in this lighter first half. But Moja Prva Ljubav is the real jewel here — the band’s debut single and the most well-known song on the record. It’s reggae-infused pop done right, riding a warm brass groove straight into the collective Ex-YU memory bank.

But after that, the mood shifts. Noć U Gradu feels like a sonic detour — frantic drums, swirling keys, and jarring trumpet lines create a sense of panic more than polish. It’s messy but in a way that hints at bigger ambitions. Then Crni Žbir drops, and suddenly we’re somewhere else entirely: dark and psychedelic. The two-tone sheen is gone, replaced by tension and murky guitar work.

By Duhovi, the record has undergone a complete transformation. It begins mysteriously and slowly, and ends in a surreal soundscape of murmured dialogue and ghostly shrieking, all fading into a void. The first time I heard it, I genuinely thought something was wrong with my headphones… That sense of surprise — of not knowing what to expect—is exactly what makes this second half so compelling.

The closing track Lice is unlike anything else on the album. A slow, ballad-like meditation with off-kilter vocals, sparse drumming, and alt-rock guitar, it evolves into an atmospheric, progressive piece. Saxophone, keys, and ambient textures float in and out until the album ends—not with a bang, but with a haunting kind of grace. It’s the clearest glimpse yet of the band’s future brilliance. You can hear Bolero forming in the distance.

And that’s the tension of Haustor. The album doesn’t fully reconcile its two halves — pop on one end, experimental on the other. Still, the rawness is part of the charm. Later records would refine this balance, but the debut’s unpolished nature represents a sketchbook full of ideas — some clean, some messy, all interesting.

Soon after, they’d open for Gang of Four in Zagreb alongside Šarlo Akrobata — a moment that feels almost too perfect in hindsight.

This debut may not be their best (I’d still give that crown to Bolero), but it’s the essential starting point of one of Yugoslavia’s most fascinating bands. Four albums, no duds, and a legacy still felt to this day.