The melancholy of resistance.

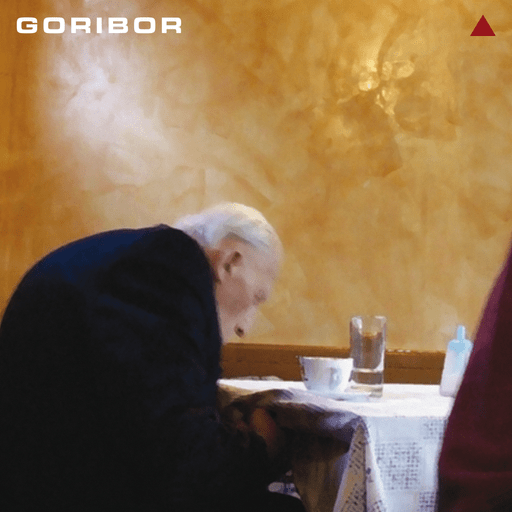

Maybe it’s in the way their songs sound like the last cigarette in a rain-soaked alley, or maybe it’s because they came from Bor — a small, industrial town in eastern Serbia that hums with the same dark static running through this record. Listening to the record, you can almost feel the weight of the place, the oppressive rhythm of small-town life, and the melancholy of landscapes both physical and existential. It’s the sound of a Krasznahorkai novel set to music — hypnotic, claustrophobic, yet utterly compelling.

Formed out of the ashes of teenage friendship and early demos, Goribor was never meant to sound clean. Aleksandar Stojković “ST” and Željko Ljubić “Pity” started playing together in the late ’80s, and by the time they reconnected a decade later, they had lived through war, exile, and enough silence to make noise feel sacred again. With a TASCAM four-track recorder and a drum machine, they began building a sound that would define them — something between rock, trip-hop, and existential poetry.

Their self-titled debut, released in 2007, is often described as the creative peak of Serbian music in the 21st century — and it’s hard to argue with that. It’s dark, hypnotic, and deeply human. The record also holds symbolic importance as the first Serbian album released on a Croatian major label (Dancing Bear) since the Yugoslav wars. A small but powerful act of cultural reconnection.

Sjajne niti sets the tone immediately — guitars shimmer like distant neon lights, looping in hypnotic repetition as ST’s voice cuts through like gravel underfoot. His nasal, raspy delivery shouldn’t work, but somehow it does. The lyrics are cryptic, philosophical, unflinching: Ko je ko i ko je kome / Šta ću ja u svemu tome — Who is who, and who is to whom / What am I to do in all this? It’s grungy, existential, noughties rock at its finest.

Hoću da živim shifts gears — half trip-hop, half garage rock, half sermon. The vocals are half-rap, half-preach, recalling Disciplina Kičme and Rage Against the Machine, filtered through the grey skies of Bor.

If there’s a moment where Goribor transcends its sonic experiments and turns into something spiritual — something painful and prophetic — it’s here. Dalaj Lama reads like a confession, a collapse, a man standing naked before the world and daring to say: I’ve seen it all, and I still don’t understand a thing.

I kao da nikad ništa nisam shvatio / I kao da nikad nisam ništa platio…

Kao da je Isus zbog dopa / Na krstu skapao…

The words spill like a fever dream — half prayer, half curse. ST writes and delivers them with a weight that feels inherited — as if every disillusioned worker, poet, and addict from the ruins of Yugoslavia is speaking through him. He oscillates between guilt and numbness, faith and mockery, until there’s nothing left but raw human exhaustion.

By the time he mutters “Kobejnu prosvirao glavu, milione u gasnu komoru poslao” ([And as if I] Blow through Cobain’s head, Sent millions to the gas chamber), we all share the same gut-wrenching hit — the narrator implicating himself (and by extension, all of us) in the cruelty of the modern world. It’s grossly uncomfortable, but that’s exactly the point.

This is where the album’s damning genius lies: not just in blending trip-hop, post-rock, and industrial textures to create beautifully layered arrangements, but in turning existential collapse into poetry. Few bands manage to capture this combination so perfectly.

From there, the record spirals deeper. Bez, the album’s haunting centrepiece, is a moment of total vulnerability. Over a minimalist trip-hop rhythm and ghostly guitar, ST murmurs a confession that feels too private to bear witness. It begins with a mundane image — his mother worrying about his pension — but quickly turns existential:

Vernik bez crkve / Građanin bez grada / Ljubavnik bez žene / Ritam bez bubnjara.

A believer without a church. A citizen without a city. A lover without a woman. A rhythm without a drummer.

It’s the sound of total displacement — a man belonging nowhere, clinging to creation as his last anchor. And yet, there’s beauty in his defiance.

Rolamo and Vreme drift through industrial textures and bluesy guitar licks. You can feel echoes of Darkwood Dub, but Goribor’s sound is even more bleak and internalised — like Portishead if they grew up in a decaying mining town.

The home stretch — Glupo and Mislim — push past fifteen minutes, pulling the listener into a hellish fog of drum & bass rhythms, spoken word fragments, and collapsing melodies. It’s ambitious, sometimes indulgent, but always compelling. Mislim, in particular, feels like a farewell — nine and a half minutes of slow-burning reflection, like the last cigarette after a journey you can’t quite forget, nor dare to remember.

A brief poem closes the album:

I prošlo je dve hiljade leta

Početak je 21. veka

A još me uvek blatnjavi puti

Vode do mojega miloga doma

And two thousand summers have passed, It’s the beginning of the 21st century, And still muddy paths, Lead me to my dear home

It’s the perfect ending — resigned, weary, yet oddly hopeful. After all the noise, anger, and confession, Goribor returns home.

At nearly 75 minutes, Goribor is a sprawling, deeply atmospheric work. It’s not meant to be digested quickly. It burns slowly, sometimes frustratingly so, but when it resonates, it’s transcendent — a record that crawls under your skin and stays there.

It stands alongside Darkwood Dub, Nine Inch Nails, Portishead, and Swans in its depth and intensity. The Krasznahorkai parallel feels apt: like his novels, the album is at times grotesque, claustrophobic, and relentless, yet breathtakingly human. As one line from Krasznahorkai’s War and War puts it, “what one ought to capture in beauty is that which is treacherous and irresistible.” Goribor does exactly that — turning darkness, despair, and existential collapse into something hauntingly, painfully beautiful. A post-modern, muddy masterpiece of existential feeling and deep despair.